Montage, UFOs, and the Illusion of Connection

Ufology architects... stop already, we see behind the illusion

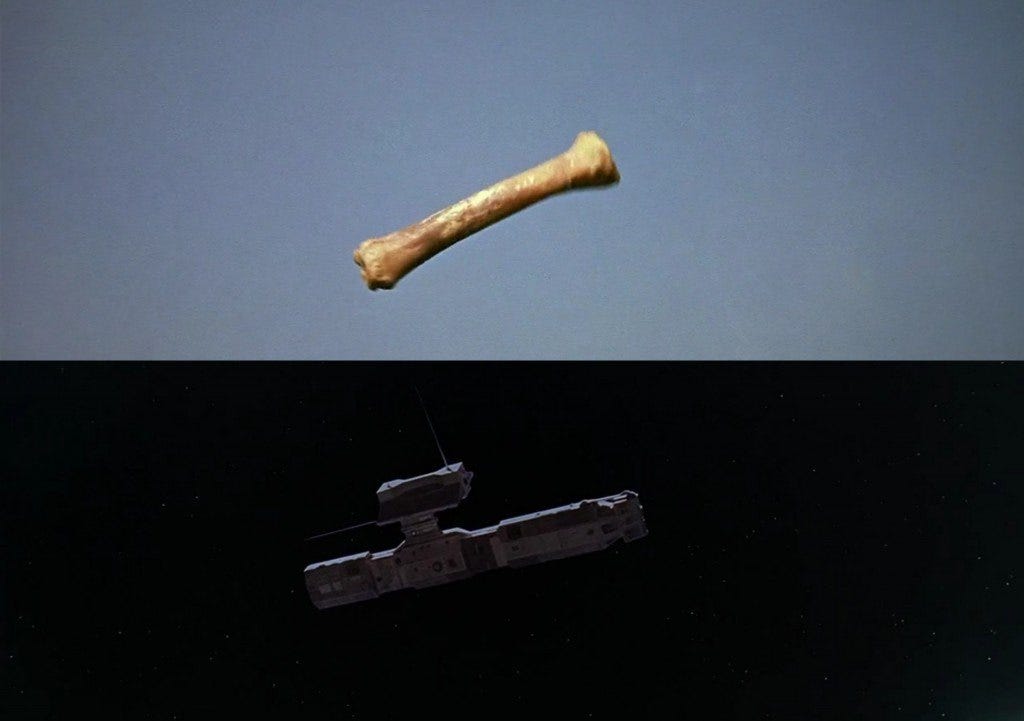

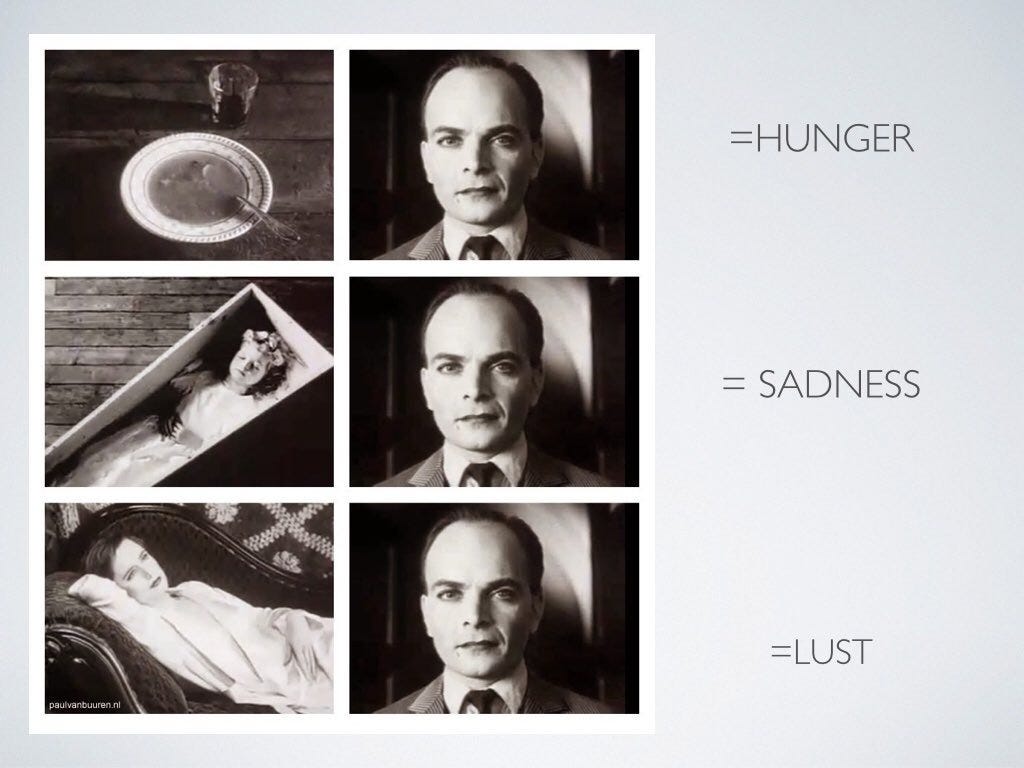

There’s a well-known technique in film theory called montage — the deliberate juxtaposition of two otherwise unrelated images in order to suggest a meaning, relationship, or causality that does not exist organically between them. The most famous example comes from Soviet filmmaker Lev Kuleshov, who demonstrated that viewers would infer emotion or story depending on what image followed an expressionless face: a bowl of soup, a dead child, a woman reclining. The face remained the same, but the context reshaped the audience’s interpretation.

Montage is not just a tool of cinema — it is a powerful instrument of suggestion, especially in media, advertisements, and disinformation. It works quickly, subconsciously. It creates a frame of association without ever explicitly claiming one.

A recent example: Lue Elizondo, who I know to be an intelligent man with integrity, former head of the Pentagon’s AATIP program, circulated a photo of what appeared to be a saucer. I believe that his intentions in showing the photo are sincere. However, and this is how this technque works, it was later revealed to be a lens reflection, not a craft. The photo was paired in online spaces and commentary with testimony from legitimate government insiders and military personnel. This pairing — the speculative and the credible — created a montage effect: the photo and the testimonies were never causally linked, but the visual adjacency implied endorsement. That’s montage.

And today, this same thing happened to me.

My book American Cosmic was cited in a recent article in the Daily Mail, placed side by side with David Grusch’s claims of a Vatican-linked crash retrieval. My work, based on years of research and published by Oxford University Press in 2019, has no relationship to Grusch’s claims — which are recent, and still under investigation. Yet, by appearing adjacent in text and image, the association is implied.

As the person who did multi-year research into Vatican manuscripts and documents, I think this latest association is deceptive.

This is how montage works. Not just in film, but in the shaping of public memory and perception. It’s subtle, powerful, and not always intentional. But it creates what feels like truth. And once that image-pairing occurs — especially in a high-emotion context like UFOs — the connection becomes nearly impossible to undo.

We need to become literate in this. Not just in narrative theory, but in the mechanics of suggestion. Because in this field, montage is a common tool — sometimes used with good intentions, sometimes not — and those of us doing serious research are increasingly being swept into associations we never made.

And here’s the irony: American Cosmic was written, in part, to reveal how meaning is manufactured — how belief systems, symbols, and narratives are constructed through framing, omission, and yes, montage. It was an attempt to show how the sacred and the speculative are fused in the age of advanced media.

Now, that very book is being used — unintentionally or not — to participate in the very techniques it warned about.

This isn’t about malice. It’s about literacy. When the tools of montage, framing, and narrative proximity are deployed without reflection, they shape public belief more powerfully than any argument ever could. That’s why it matters to name the method. Because meaning, in our age, is often created not by what is said — but by what is placed next to what.

If Piranesi isn’t on your radar yet, I highly recommend it. Susanna Clarke’s novel—winner of the 2021 Women’s Prize for Fiction—centers on her “most famous idea, the Theory of Other Worlds... ‘Somewhere... there must be a passage, a door between us and wherever magic had gone.’” Guided by this theory, the mysterious Arne-Sayles gathers a group of acolytes and devises a way to enter these Other Worlds. Piranesi, with its haunting labyrinth and themes of memory and revelation, is deeply inspired by Plato’s Allegory of the Cave—and the journey of escape into the light.

Well said, Diana.